Whipple Procedure (Pancreaticoduodenectomy)

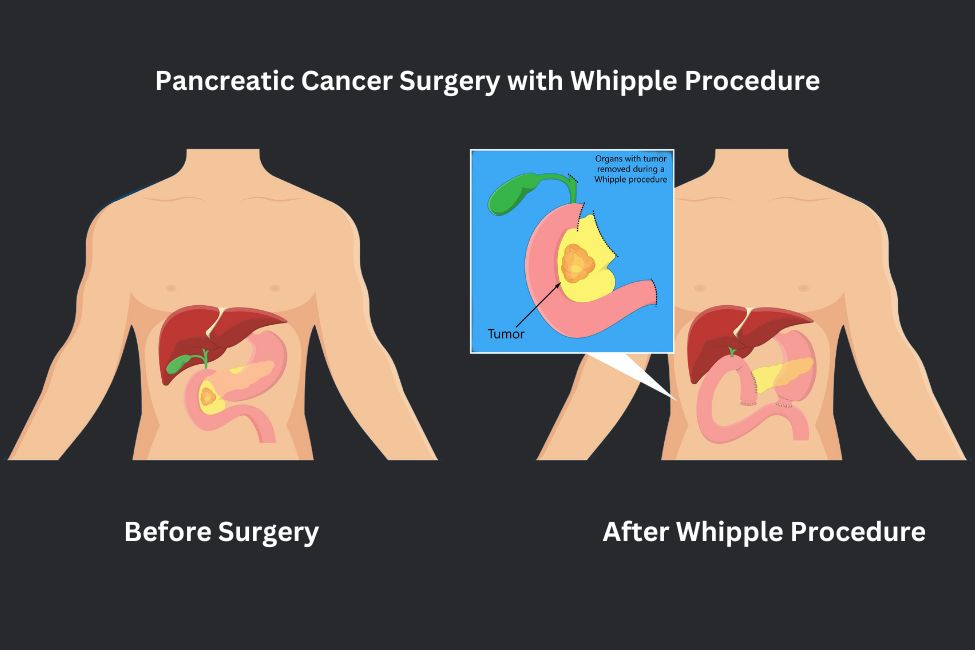

The Whipple procedure is indicated when a malignancy (tumor) is found in the head of the pancreas. Along with the cancer itself, the surgeon will remove the head of the pancreas, part of the duodenum or small intestine, and the gallbladder. There are two commonly performed variants of the Whipple procedure:

- The Classic Whipple. Along with the organs and tissue removed in all Whipple procedures, the lower third of the stomach will be removed as well.

- The Pylorus Preserving Whipple. During this more recent procedure variant, the entire stomach is spared, including the pyloric valve that connects the stomach to the small intestine.

The first tube is next to the new connections formed in the abdomen. Approximately 5% of patients may develop a leak; however, these leaks rarely require a follow-up operation. Leaking fluid must be aspirated as sepsis (infection) can occur if fluid pools in the abdomen. The drain will be able to catch much of the leaking fluid, reducing the risk of infection. This tube will usually be removed about a month after surgery or when any leak has stopped.

The second (gastrostomy) tube is directly connected to the stomach. A common side-effect of the Whipple procedure is a temporary reduction of stomach function – it may not empty effectively. We help ensure the most comfortable stomach drainage using this tube. While most patients transition to solid foods within a week, some patients (up to 15%) may not regain their normal stomach function for longer.

The tubes are taped to the patient’s side to minimize visibility and are usually removed at an office visit after a couple of weeks with little or no discomfort.

Risks and Considerations

- Bleeding: While we take precautions to minimize this risk, the Whipple procedure has a slight chance of bleeding.

- Infection: Infection is a possible complication of any surgery. However, because of the complexity and scope of the procedure, the risk of infection is slightly higher. These infections are varied and can present at the wound site, in the urinary tract, or as an abdominal abscess. Infections are treated swiftly and seriously.

- Blood clots: Blood clots in the leg are also a possibility due to both the cancer itself and the surgery to treat it – this is known as Deep Vein Thrombosis or DVT. Patients will take blood thinners throughout their hospital stay to mitigate blood clots.

- Diabetes: One of the main functions of the pancreas is to secrete insulin and thus control blood sugar. The ability to generate insulin-producing cells is compromised when removing the pancreas. As a result, some patients who had normal blood sugar levels before surgery will develop diabetes. Diet-controlled diabetics risk needing to start insulin after surgery. Almost all patients on oral hypoglycemic agents will need insulin.

Most patients will require a hospital stay of 7-10 days. This is necessary to ensure that stomach function returns to normal. After discharge from the hospital, patients can expect a full recovery in approximately two months.

Postoperative Dietary Expectations of the Whipple Procedure

Patients will be encouraged to drink clear liquid fluids for the first day or two after the procedure. During this time, the gastrostomy tube will be left open, and the contents will drain into a collection bag. On the second or third day, the tube will be clamped to see how much fluid remains in the stomach after 6 hours. Once under 300 mL remains, we move on to a 24-hour clamp. If the fluid levels are still low, we advance to additional liquids and eventually soft then solid foods depending on how well the patient feels. The hospital stay will ultimately be determined by how well the stomach functions.

Once home, patients will continue to regain their stomach function and can speed up the process by eating small, frequent meals throughout the day rather than fewer larger meals. Most patients will be able to tolerate solid food within approximately six weeks of the procedure.